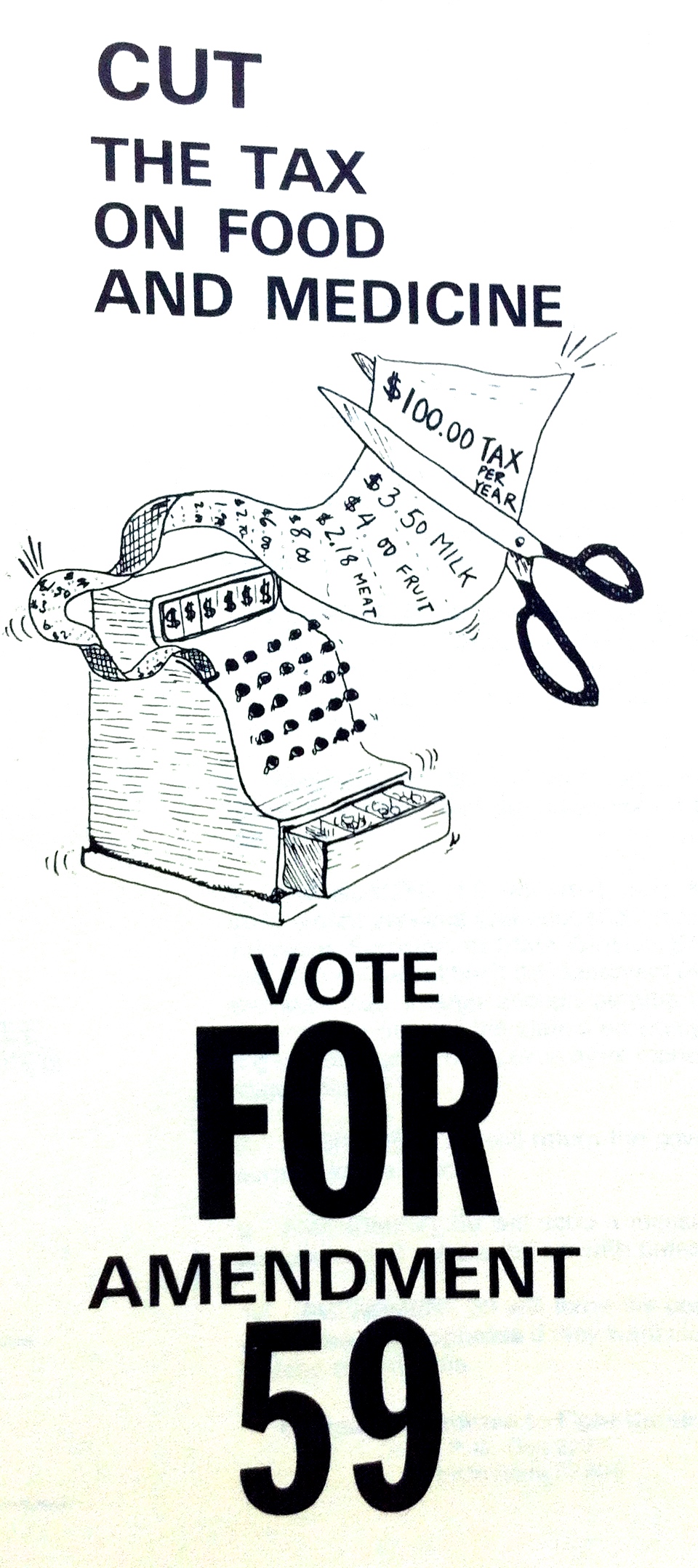

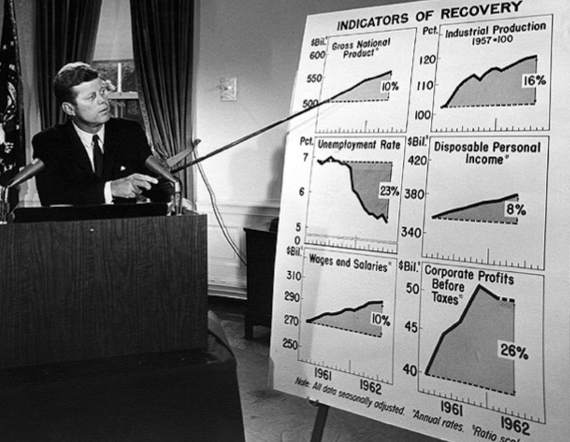

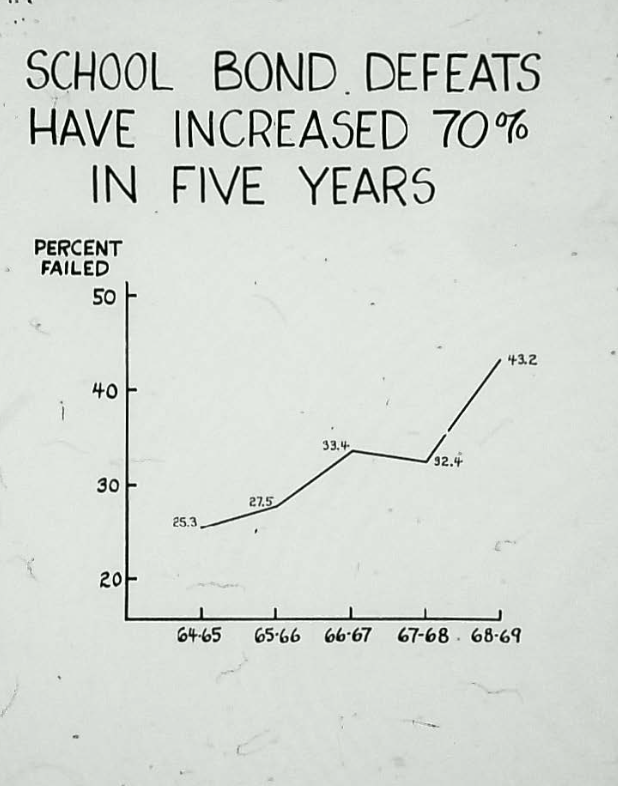

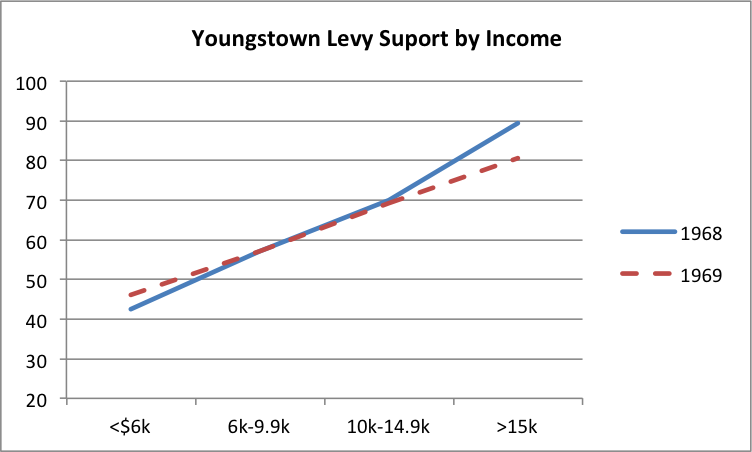

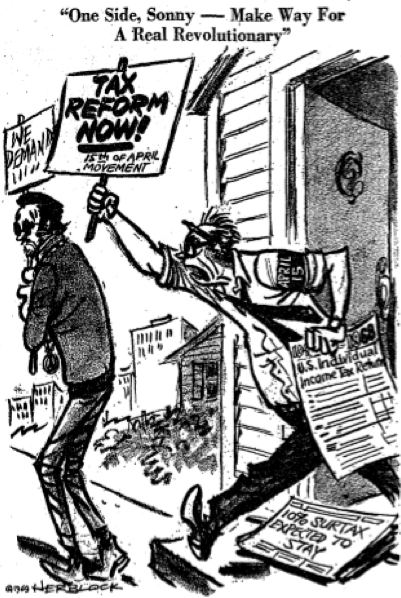

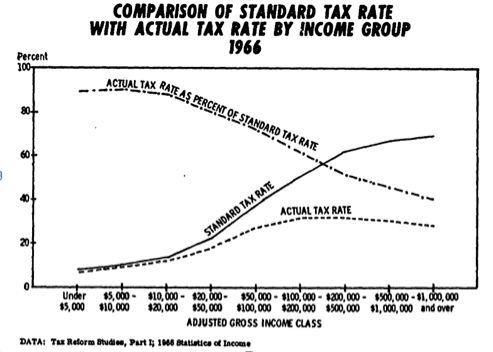

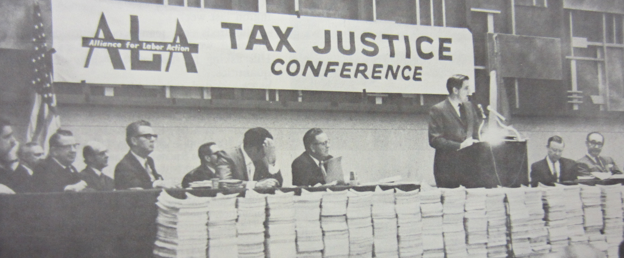

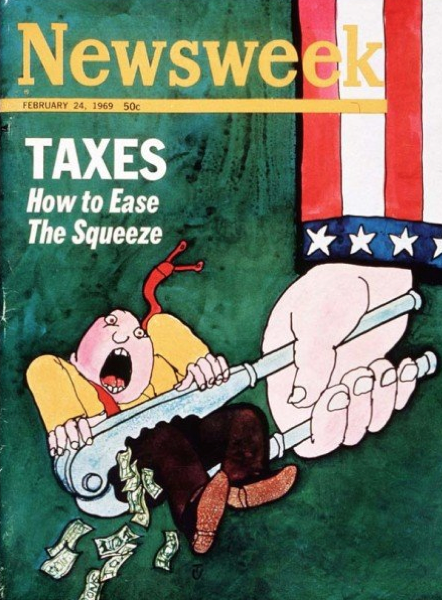

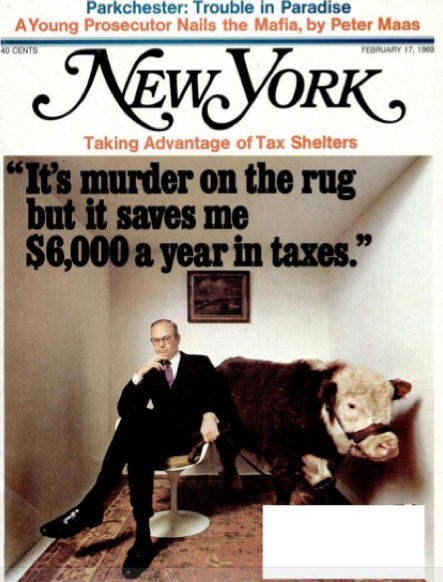

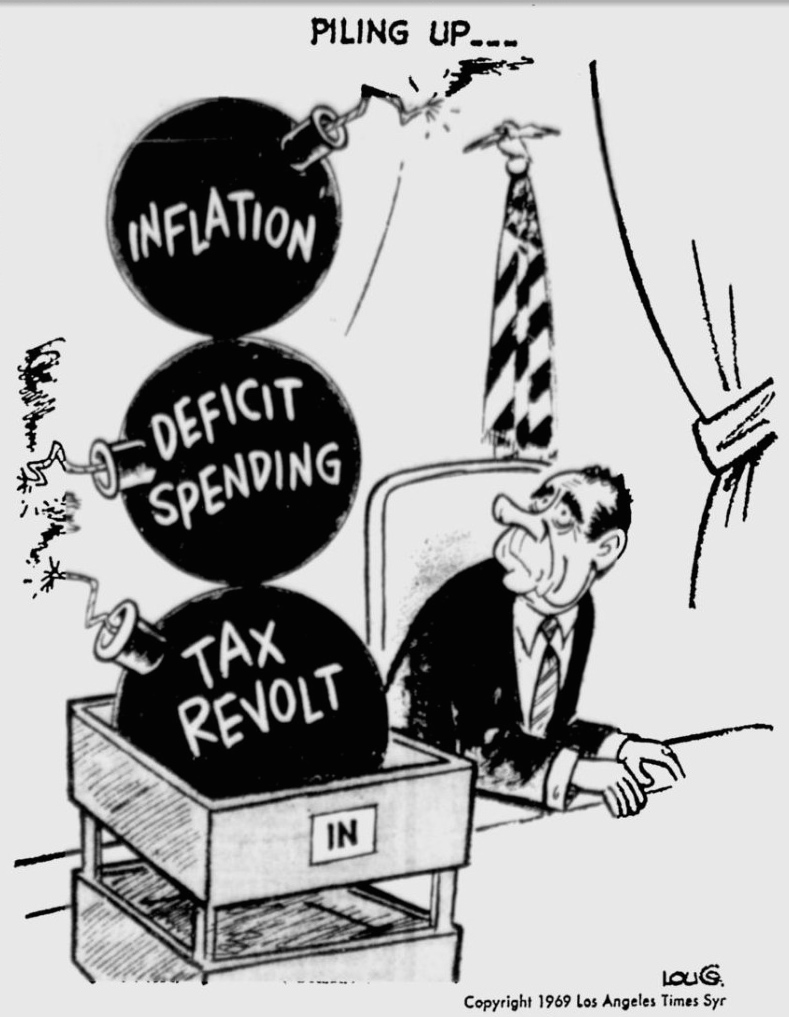

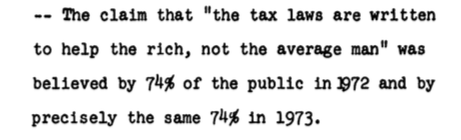

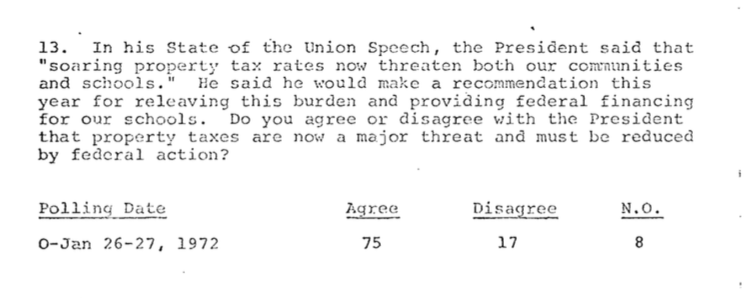

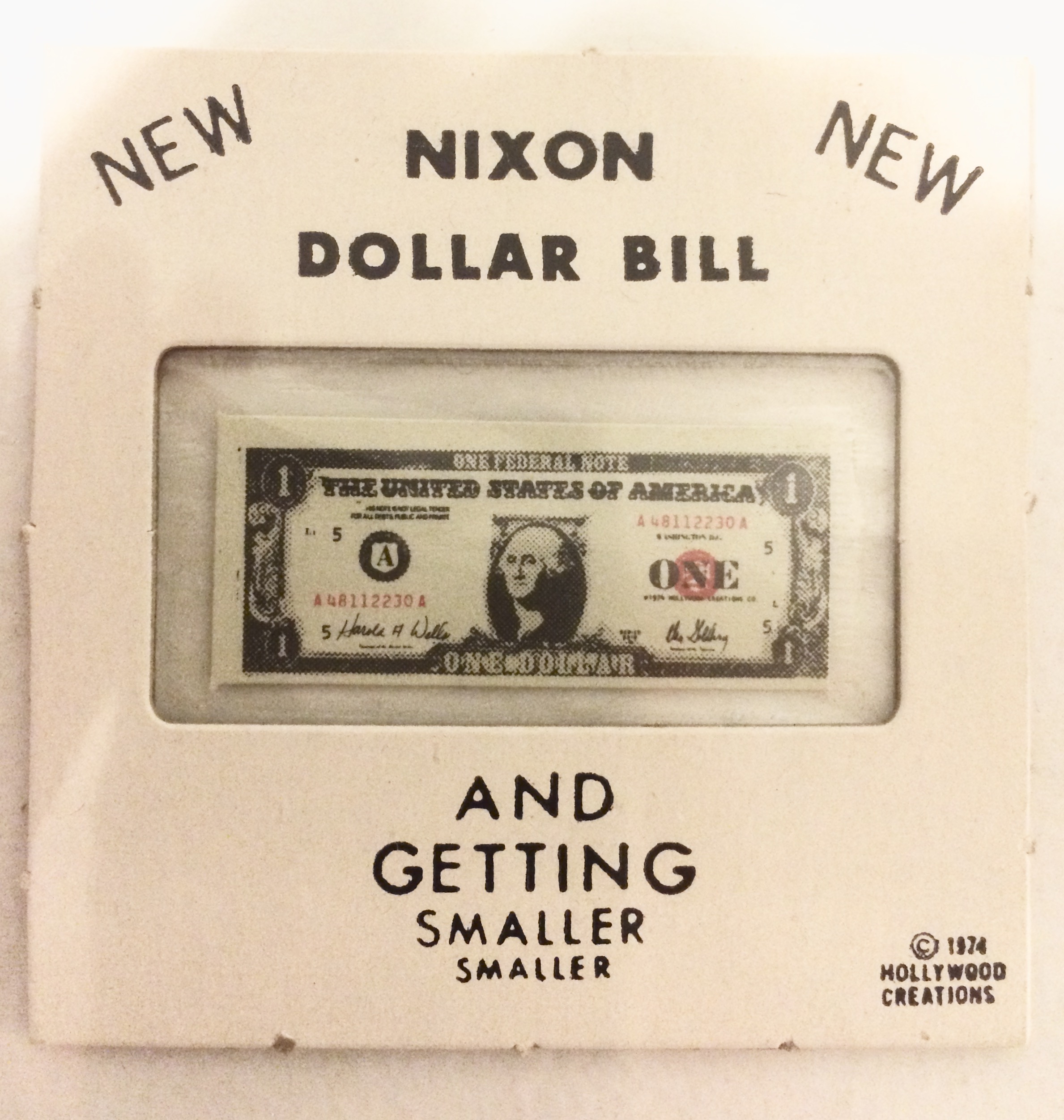

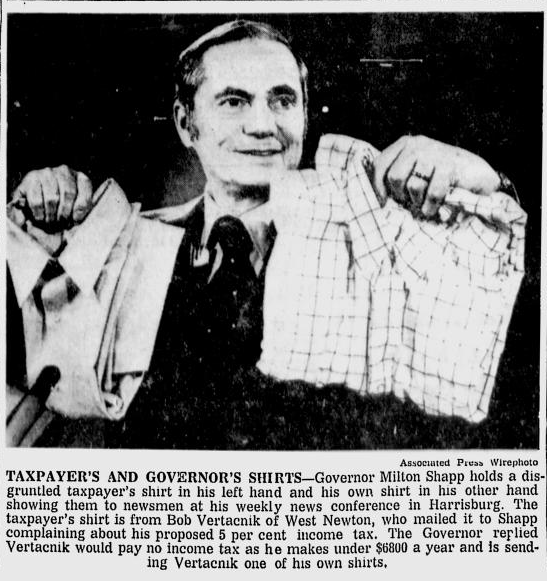

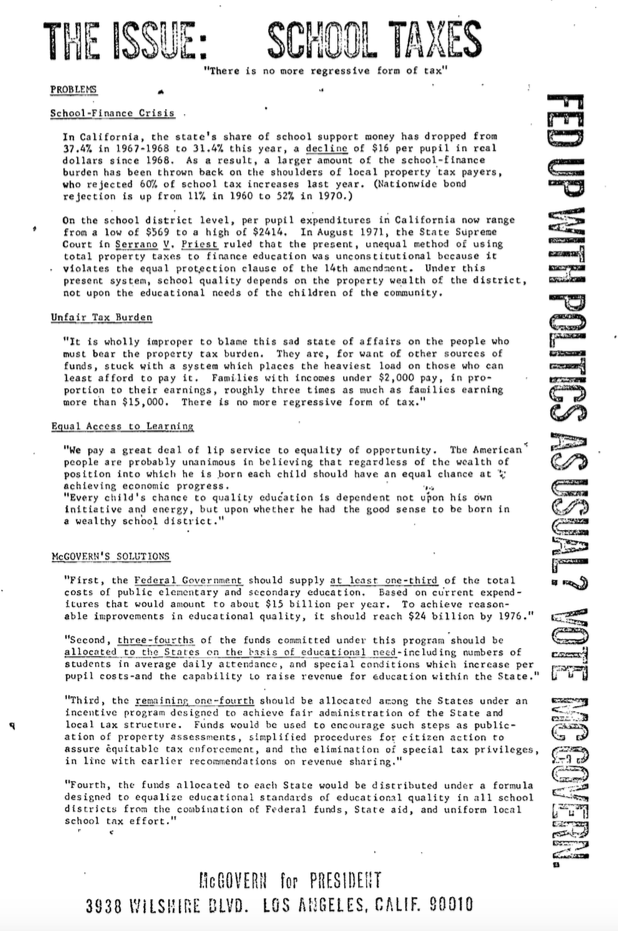

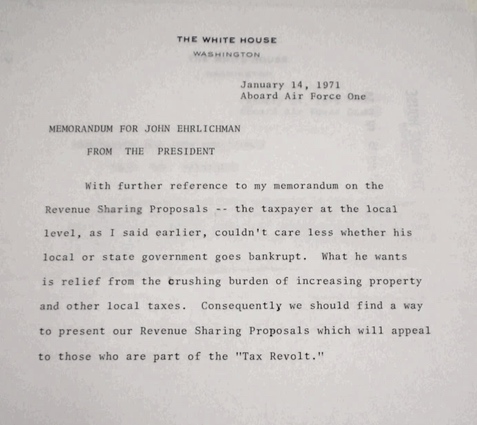

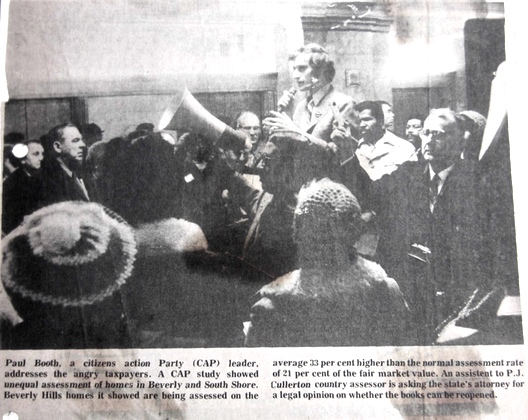

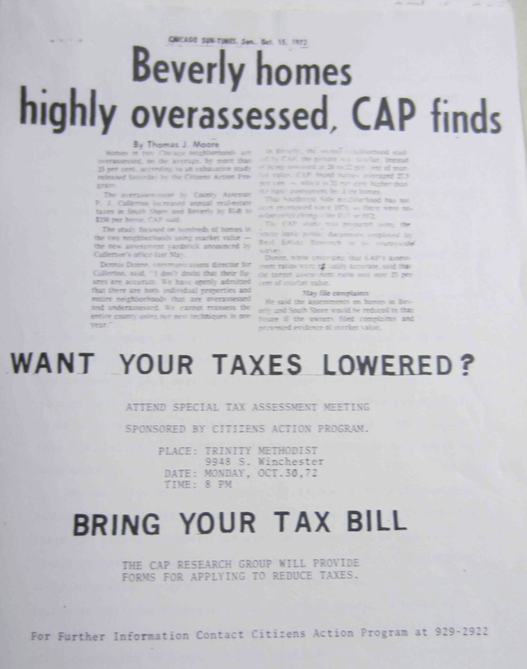

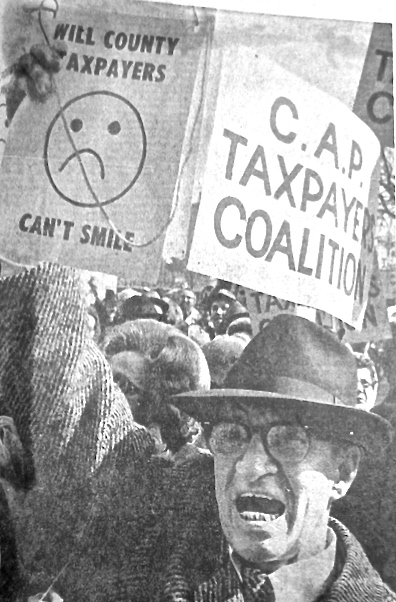

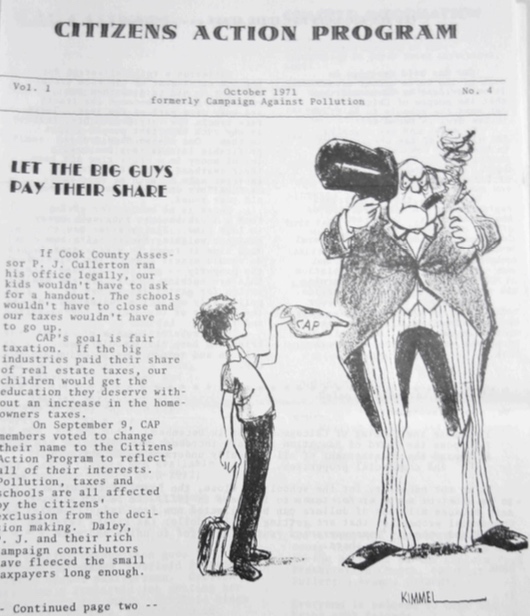

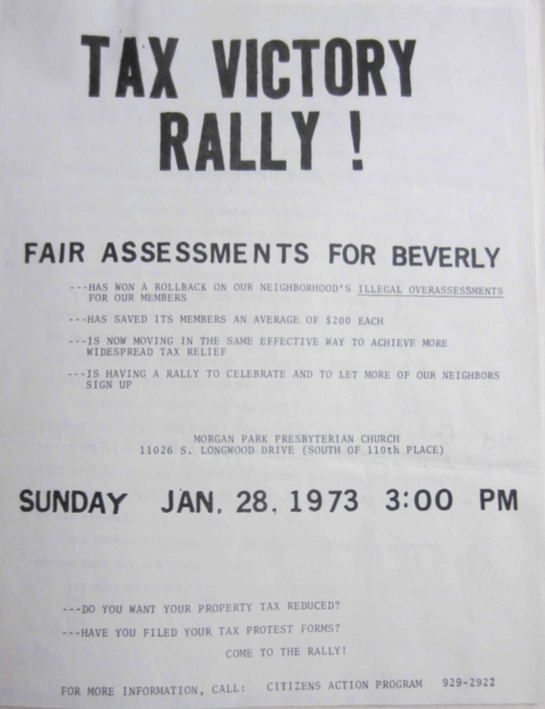

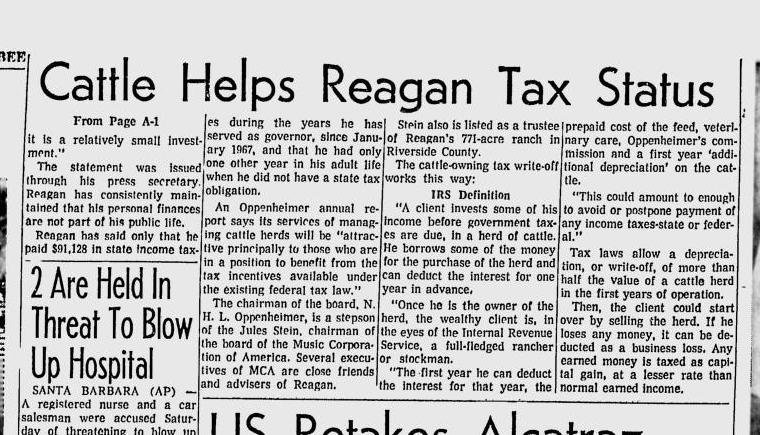

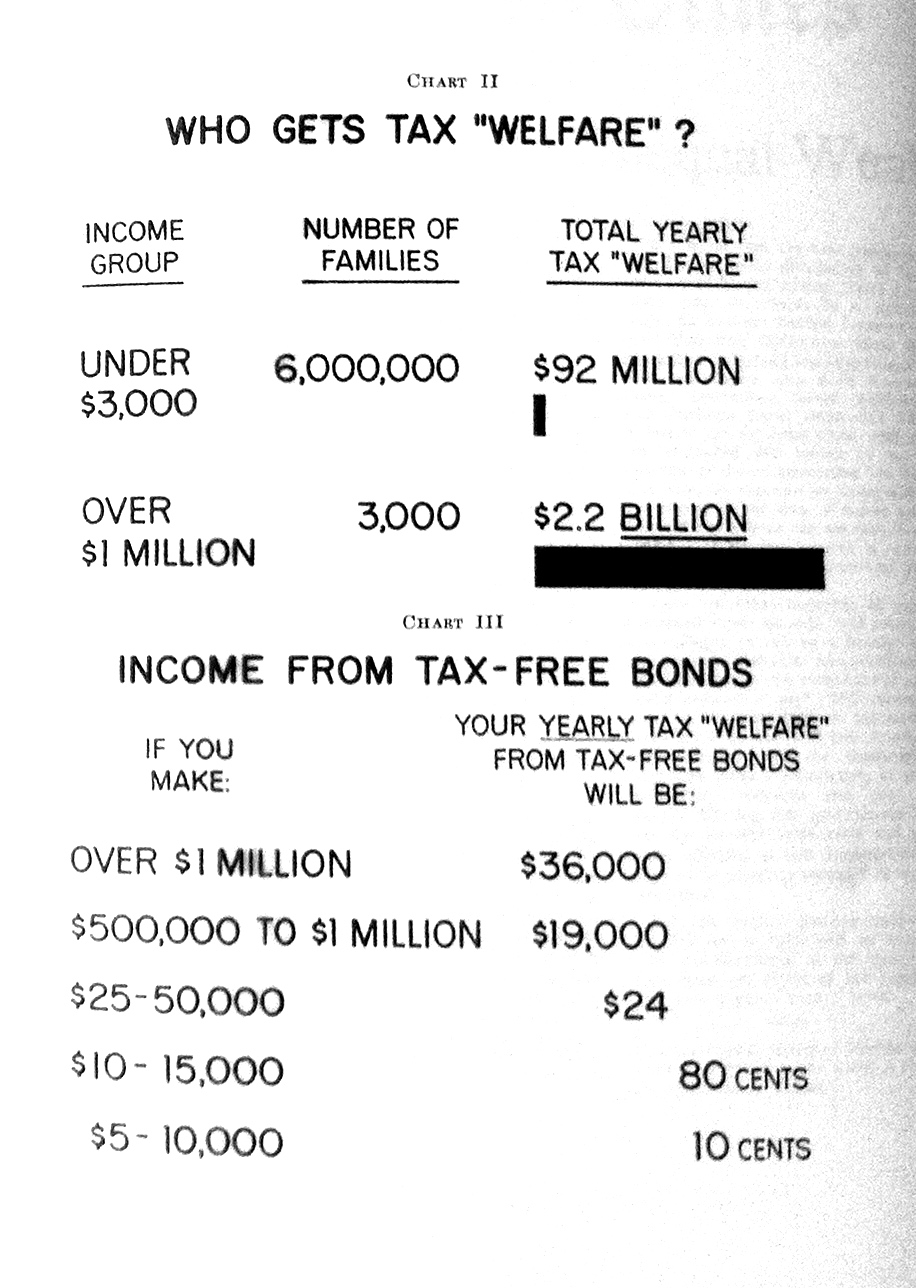

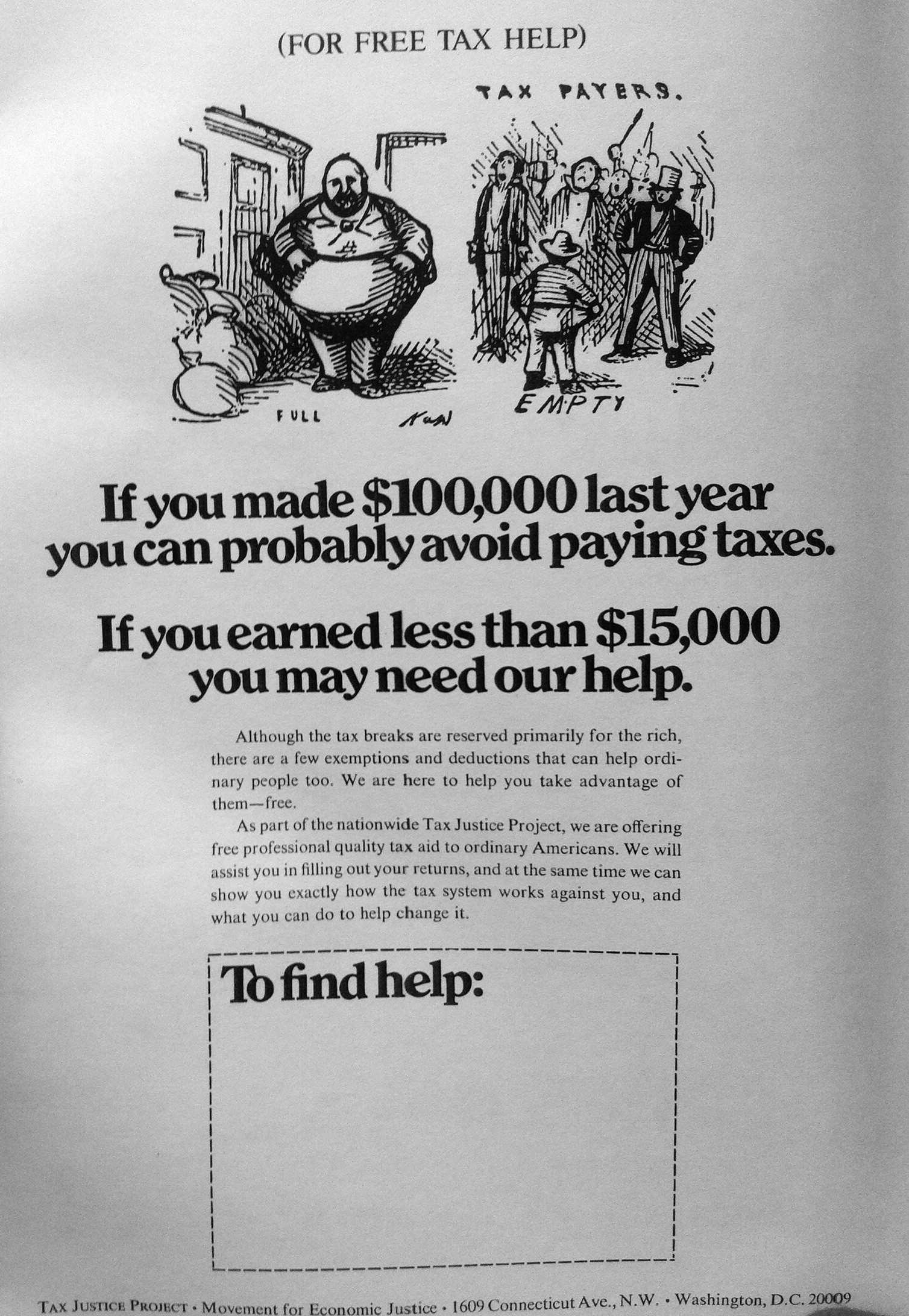

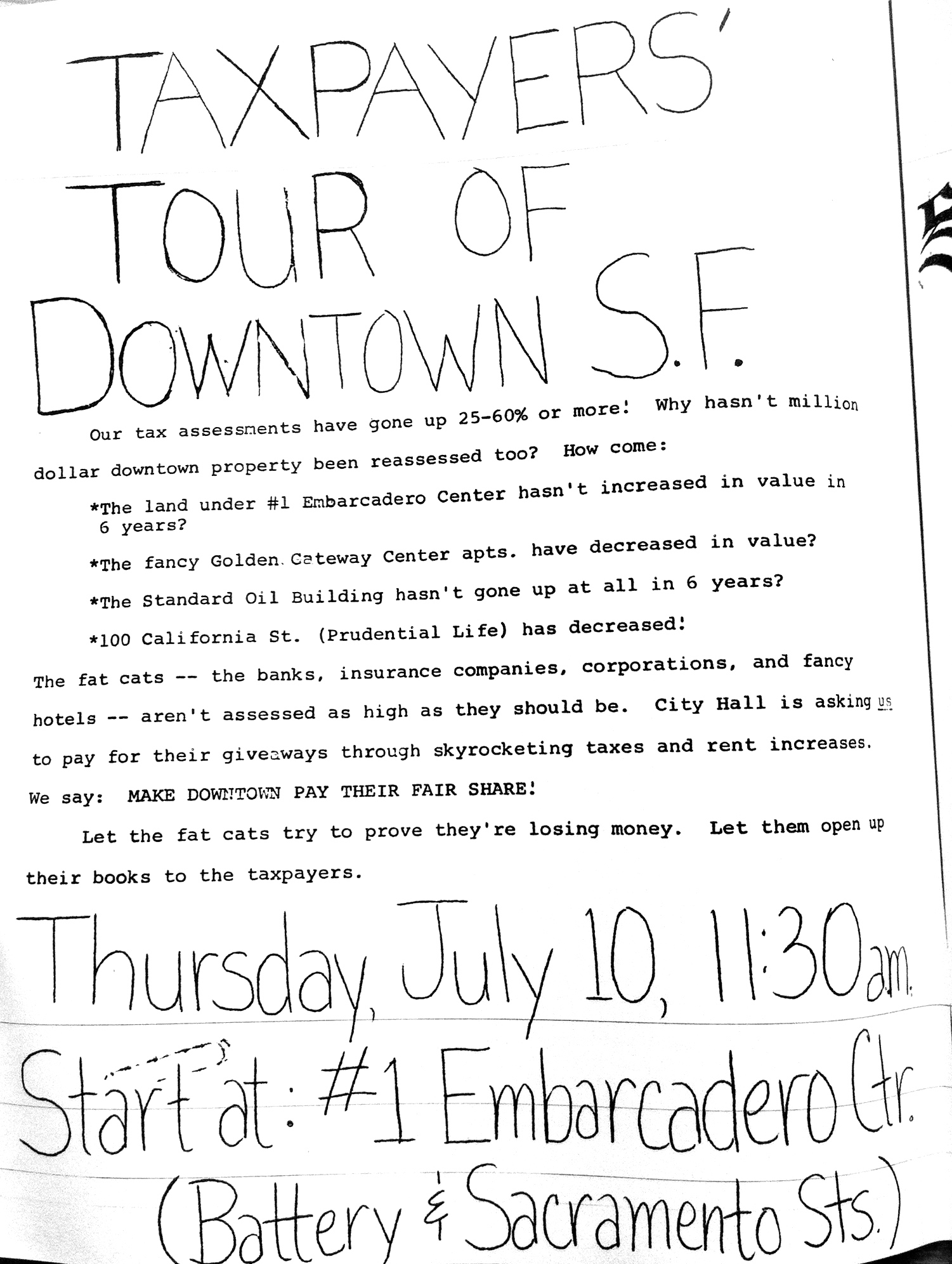

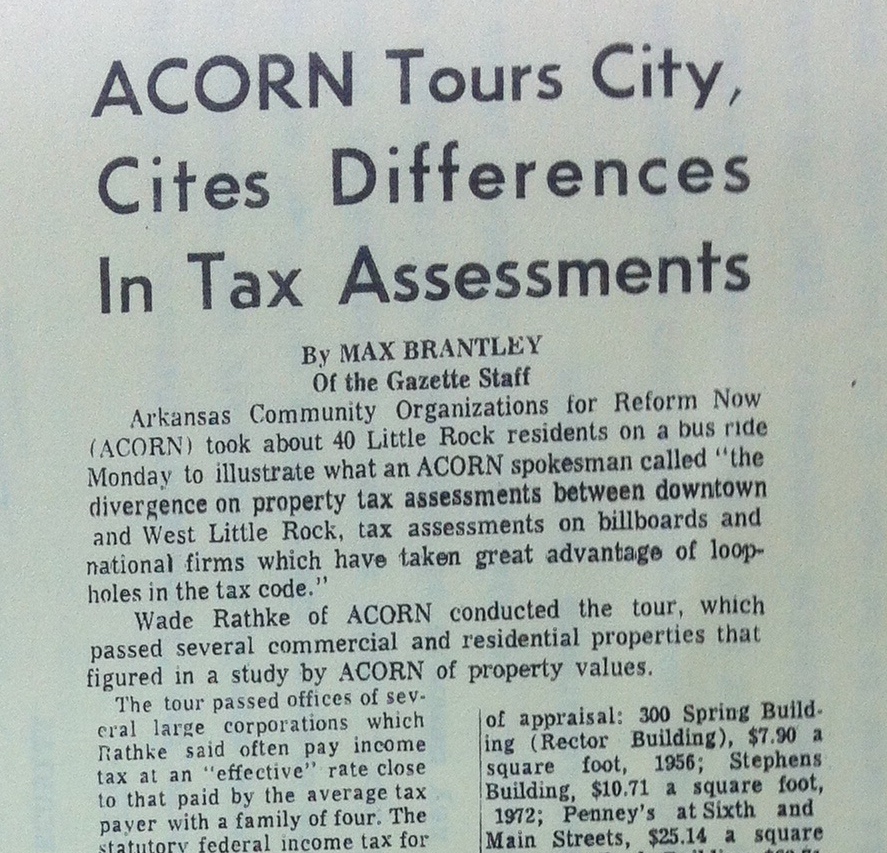

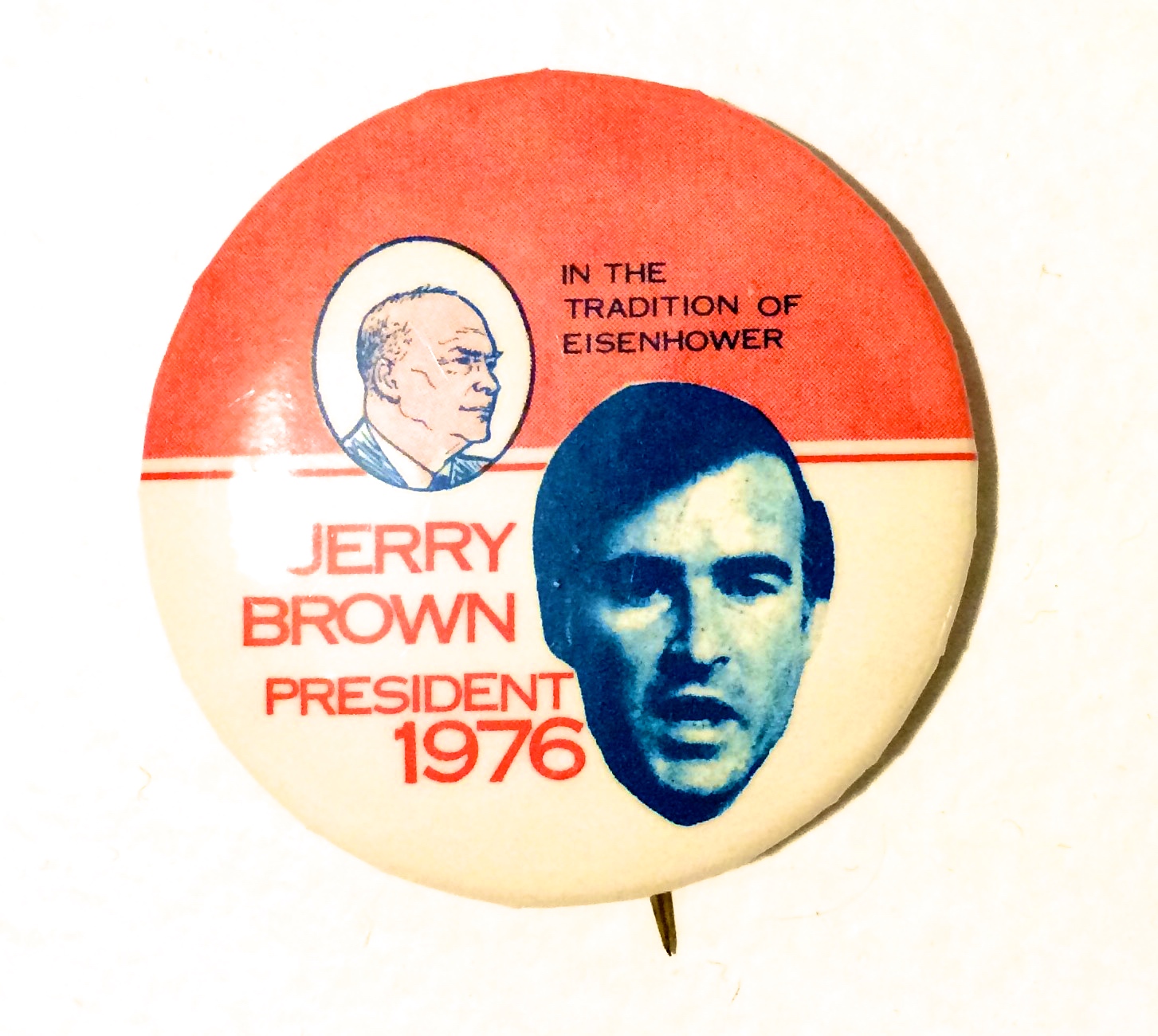

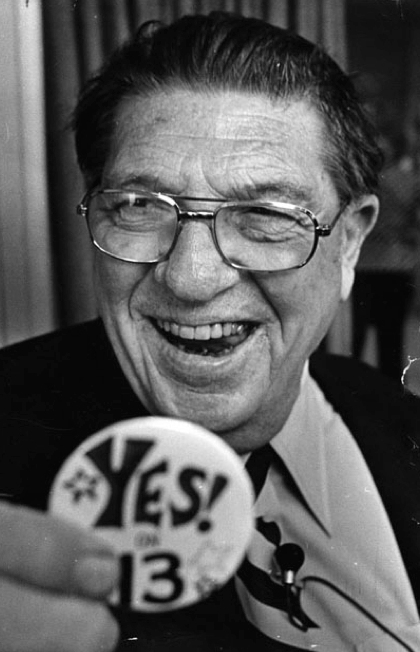

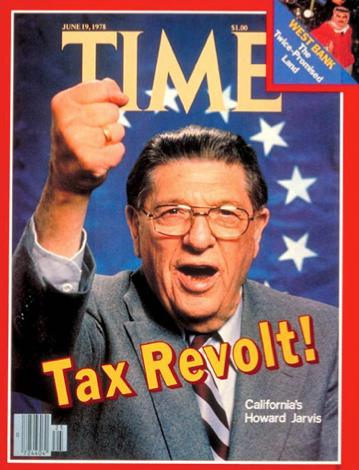

My book manuscript examines the causes of the “tax revolt” of the 1970s – including its best-known event, the passage of California’s Proposition 13 in 1978 – as well as the significance of the revolt for electoral realignment, economic and racial inequality, and the broader political economy of the modern United States. It illustrates how the relationships between party politics, social movement activism, policymaking, and public opinion shaped the system of American “fiscal federalism” from the 1960s through the 1980s. For decades prior to Prop 13, regressive state, local, and payroll taxes rose to record highs. Inflation exacerbated this “pocketbook squeeze” on lower- and middle-income Americans, while exposés of tax “loopholes” that benefitted the wealthy stoked public anger. By the mid-1960s, voters across the country and across demographic groups engaged in a now-forgotten revolt, defeating local property tax levies at record-high rates. Left-leaning activists – including Ralph Nader, Saul Alinsky, and George Wiley – were the first to successfully harness the public’s tax discontent, both organizationally and legislatively, by framing taxes in terms of distributional fairness. Within the next decade, however, American tax politics would come to be defined by initiatives like Prop 13 and the conservatives, including Ronald Reagan and Milton Friedman, who championed them. Drawing on material from more than a dozen archives across the country and mixed-method analyses of local, state, and national voting and opinion data, my manuscript explains the puzzle of how a movement that began on the left came to be seen as a key cause of the “rise of the right.”

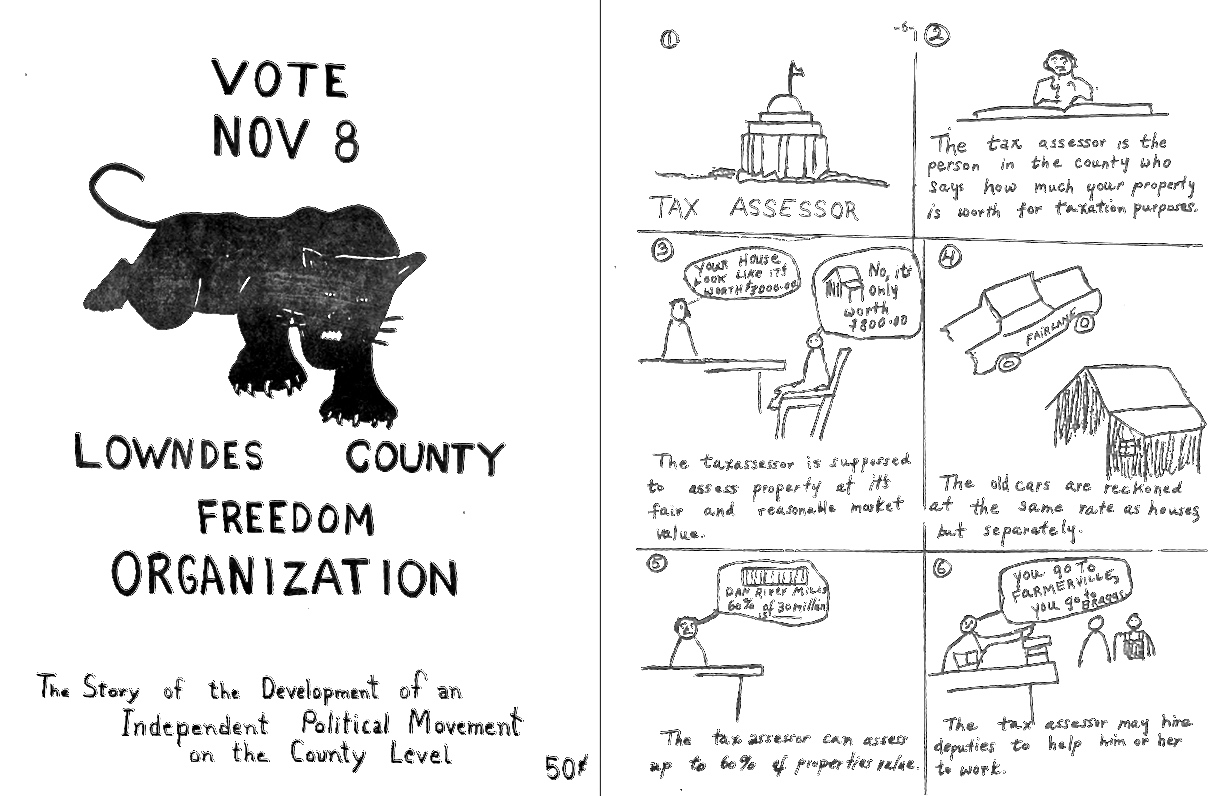

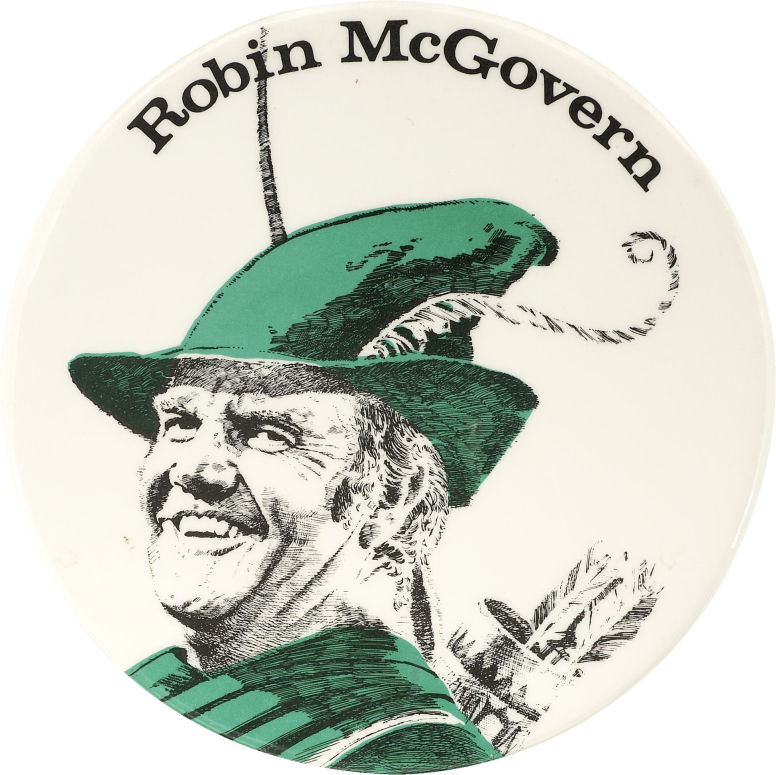

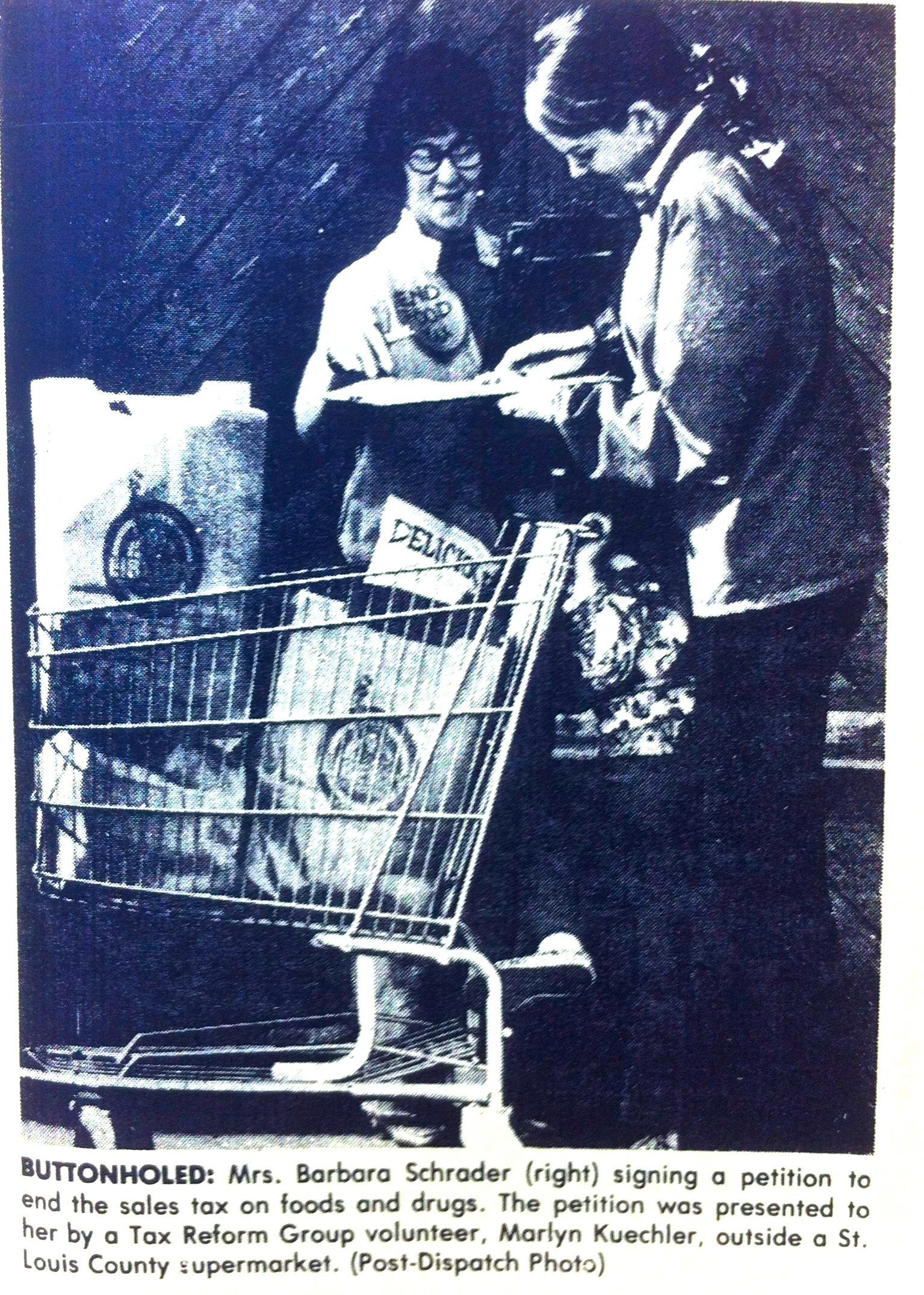

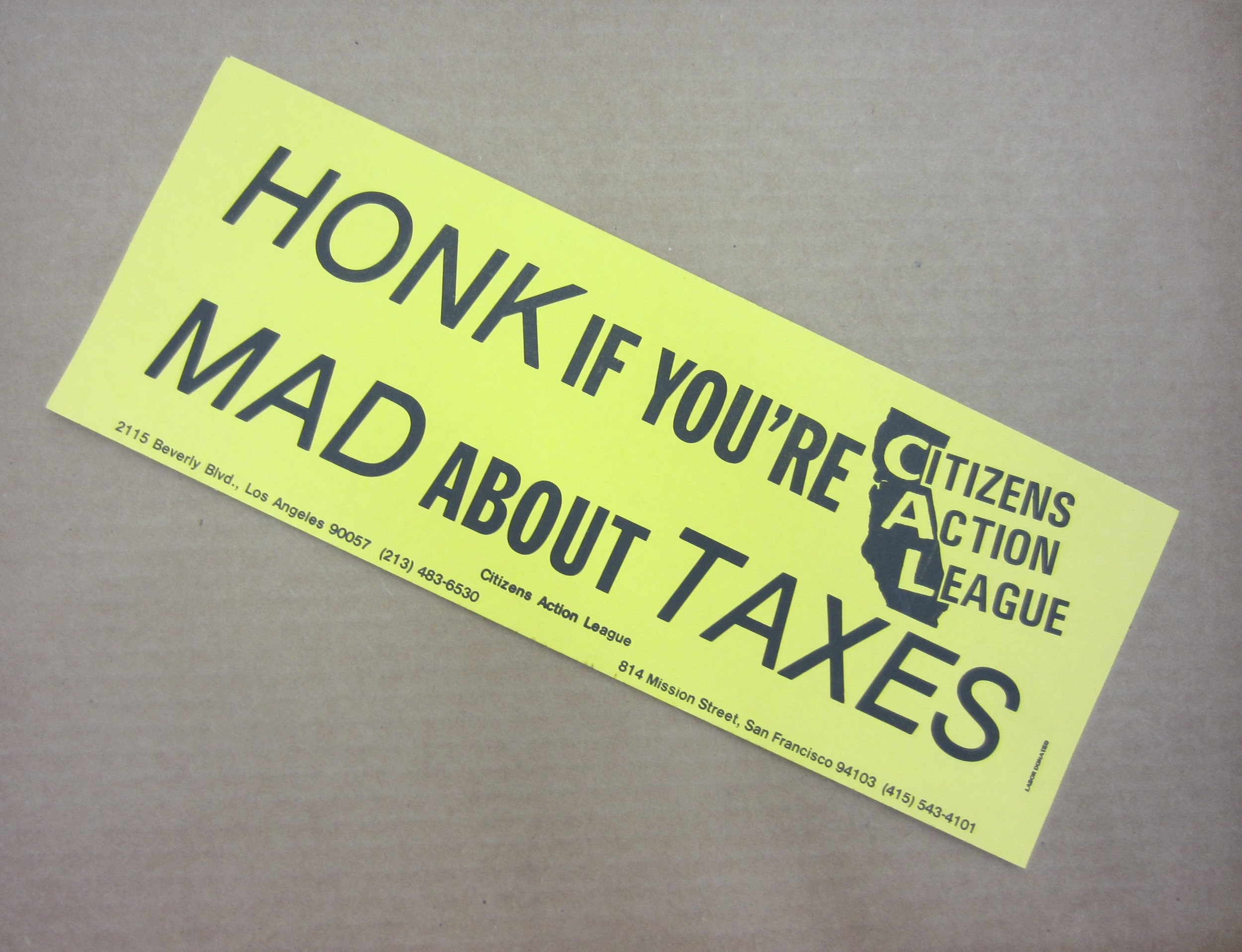

In solving this puzzle, my project departs significantly from the existing literature authored by historians and social scientists on both the tax revolt and the transformation of American politics and economics since the 1960s more broadly. Recently, historians have begun casting the “long 1970s” as a “pivotal decade.” In these accounts, the tax revolt assumes a key place in the conservative “backlash” against the racial and economic liberalism of the 1960s, presaging the “fall of the New Deal order” and culminating not only in Prop 13, but also in later events like Reagan’s 1981 tax cuts, the recent “Tea Party” movement, and the election of Donald Trump. The tax revolt, in this view, is emblematic of whites’ resentment at their hard-earned tax dollars being redirected by liberal government to welfare recipients and people of color. Likewise, sociologists and political scientists have portrayed both the tax revolt and the concomitant welfare state retrenchment as the inevitable outcome of longstanding American social arrangements and political institutions, including the United States’ “adversarial” economic policies, use of “informal” tax subsidies, and racialized welfare politics. My manuscript challenges these accounts. It demonstrates that the tax revolt was a movement of economic populism that more often tilted to the left than to the right. It also dispels the myth that a white backlash created the revolt. In fact, polls throughout the decade consistently showed that tax discontent cut across lines of race, class, gender, and ideology, while activists from the black freedom struggle were among the first to make taxes a grassroots issue. My project’s most important conclusions are that genuine pocketbook frustrations drove the tax revolt of the 1970s and that the answer to the puzzle of how the tax revolt eventually came to be seen as synonymous with the political right lies in the relationship between party politics, grassroots activism, and public opinion. Specifically, the Democratic Party’s reluctance to embrace the tax politics of left-leaning tax activists and the Republican Party’s willingness to champion the demands of conservative tax activists tilted tax policymaking – but not public opinion or grassroots activism – in a more conservative direction as the decade wore on. While most voters preferred more progressive solutions to the pocketbook squeeze, they ultimately supported conservative tax-cutting measures out of pocketbook necessity, rather than ideological fervor. As one left-leaning California tax activist said after reluctantly deciding to cast a vote for the property tax-slashing Prop 13, “I want to keep my home.”

My book manuscript is underunder advance contract for publication in the University of Pennsylvania Press’s Politics and Culture in Modern America series. An edited version of the first chapter was published as a Journal of Policy History article, “Stirrings of Revolt: Regressive Levies, the Pocketbook Squeeze, and the 1960s Roots of the 1970s Tax Revolt” in April 2020.